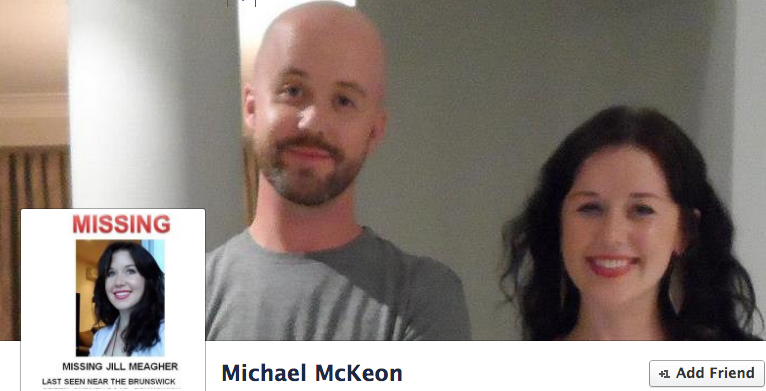

Jill Meagher’s recent disappearance and death has touched many people. How do we know? Because social media has been a platform for the sharing of news and emotional comments from an enormous number of people. Not only family and friends shared Jill’s photo on Facebook, it seems the shock of Jill’s disappearance and fear for her life has touched many others, and they have been publicly expressing their reactions. The Facebook page set up to find Jill currently has over 83,000 likes.

There’s no denying that social media – in particular, Facebook and Twitter – have been harnessed by people who believe that dissemination of information through these media will reach the widest audience – and hopefully make a difference to the life of Jill Meagher. Sadly, although this journalism from the ground has allegedly aided the search for Jill, and led to the arrest of Adrian Ernest Bayley, the outcome has been tragic, and people have continued to use social media for their outpouring of sadness and condolences to Jill’s family and friends. Now the Facebook and Twitter updates point to the possibility of interference with the legal proceedings if people continue to use social media as a platform for anger and accusation.

“Overnight, the sentiment was very much of grief and sadness and now this morning, anger is starting creep into what is being shared and re-shared.”

With that anger comes responsibility to social media users, who become content publishers when they post. That may require a knowledge of media law.

Thomas Meagher, Jill’s husband, today urged people to consider what they posted on Twitter and Facebook.

“While I appreciate all the support, I would just like to mention that negative comments on social media may hurt legal proceedings so please be mindful of that.”

This message has been tweeted by the Victorian Police and others today. Julie Posetti is one of these people.

Julie is a prominent journalist and journalism academic, and is currently writing a PhD dissertation on The Twitterisation of Journalism, examining social media’s transformation of professional journalism. In today’s article in The Age she explains the issues associated with public commentary about the case and the accused.

“In this particular case, it would be awful to think about the potential consequences including an incapacity to prosecute somebody because of trial by social media, for example,” said Ms Posetti, who is writing a PhD on Twitter’s role in journalism.

“We all are very familiar with the term trial by media and it’s a real problem, but we also now need to be aware of the potential implications of trial by social media.

“Practically, [and speaking] generically, as soon as a person is arrested, we need to stop talking about what we think we know about that individual because there is a risk that his or her defence lawyers could argue that there’s no possibility for a fair trial in this country for the person who’s accused, because so much information has been published.

I’m ignorant about social media laws – do we have clear and current laws in Australia relating to social media? A quick Google search led to audio and transcript of an ABC Radio National “Law Report” episode with guests Mark Pearson, Professor of Journalism at Bond University, and Julie Posetti.

Photo by Jeffery Turner on Flickr

The transcript of this episode can be read here. We should read this to our students as we discuss the whole new area of legal implications associated with the issue of personal and public blending through social media. We need to inform ourselves about these issues, and schools should be focusing more urgently on these matters as social media becomes the way the world works, not just kids on Facebook – although that needs to be dealt with too – but the way news is shared, the way businesses are run, the way projects are created and managed, the way people collaborate globally with today’s technical possibilities. Why would we put aside important curriculum to discuss social media in our classrooms? Well, as Mark Pearson says in the ABC interview,

And only last year we had a British gentleman who posted a witty tweet, or what he thought was a witty tweet, about blowing up an airport, and he was just expressing it as satire, he said, because he was frustrated that snow had stopped flights from this particular airport, but unfortunately national security and police agencies don’t always have a sense of humour, and they certainly didn’t in that case, and his house was raided, he was arrested, he was charged with national security offence and he finished up being released, of course, but he suffered a whole lot through the process and spent some time in the big house, at least temporarily, as a result of it. Something none of us need in our lives.

The implications of social media are vast and serious, but the access to the new form of ‘journalism’ is there for anyone with a phone or internet access. If teachers are uncomfortable in this new and always changing arena, then all the more reason to learn together. It’s not a fad, it’s not going to go away.

Mark Pearson explains social media law:

The basic laws are pretty much the same as they applied to journalists and media organisations in the past. So, your fundamental law of defamation, contempt, confidentiality, all of these areas, you know, the core law is still the same, it’s just that some circumstances have changed with new media and social media.

It’s so easy to post that short, quick post without thinking, and without education our young people are more likely to get into trouble. When are schools going to integrate digital citizenship into the curriculum, along with other literacies? How are we going to prepare for this as teachers?

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D_CBSR4ttqc&w=420&h=315]