Image found here

The eye is naturally drawn to things you’ve been thinking about. So it was for me last night when I was browsing my Twitter feed and came across Susan Carter Morgan‘s retweet of Angela Stockman‘s link to her article The questions we ask when we begin to teach writing on the WNY Young Writers’ Studio website. Angela asks:

“Is it possible to teach writing well if your students aren’t aware of what’s possible now? If they aren’t publishing online?”

An interesting question. Although I hadn’t exactly been phrasing it as specifically as this, I’ve been wondering about the task of teaching writing at a time when our publishing options are so many and varied; wondering whether we’re doing our students a disservice if we continue to teach writing the way we were taught. I mean without recognizing the opportunities for a broader, online audience. I’ve been rabbiting on about this for quite some time.

I also wonder why we are still predominantly text-centered with regard to storytelling options when there are so many other options for storytelling, particularly with the new digital possibilities.

“Composing isn’t just about text anymore.”

And it isn’t. That’s not to say it’s any less important to teach textual writing but there are so many other things to consider. If our students are reading stories online, enjoying graphic novels, following and creating stories in virtual worlds, then shouldn’t we be exploring these new forms of narrative with our students?

There’s a mounting list of technological applications which enable and enhance storytelling. These options incorporate visual and digital literacies, amongst others, but writing is still the crux, that is, creating plot, characters, setting. The story itself, is still a matter of writing. As Angela states:

“I don’t focus on genre or the writing itself at first either. I find myself asking questions about who the writers are, what kind of difference they want to make with their words, and for who.”

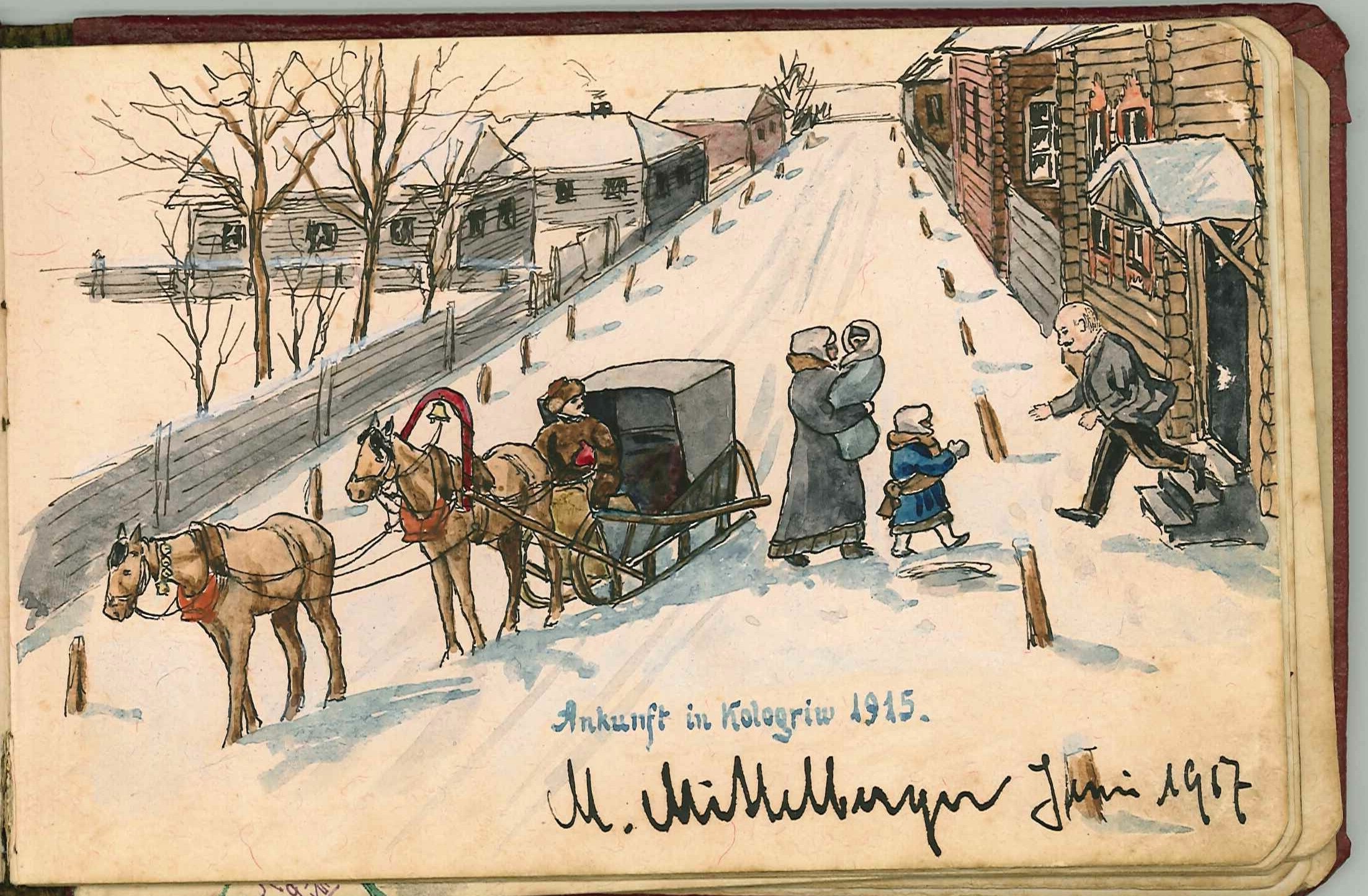

“When my grandmother died, she left behind her childhood journals and a whole bunch of letters,” someone mentions to me quietly. “Seeing her handwriting helps me hear her voice. It keeps her alive.” And I appreciate this. I know that when I look at my daughter’s blog and when I skim through her Flickr stream or her Facebook updates, I experience the same feeling. For me, it isn’t about the ink. But I’m not the only audience the writers I work with will have. In fact, one thing I do know for certain is that if I’m doing my job right, they won’t be writing for me—they’ll be writing for other people, and their purposes and the tools they will use to connect with them will vary. As a teacher, what I think and what I need doesn’t matter at all. It’s all about the writer.”

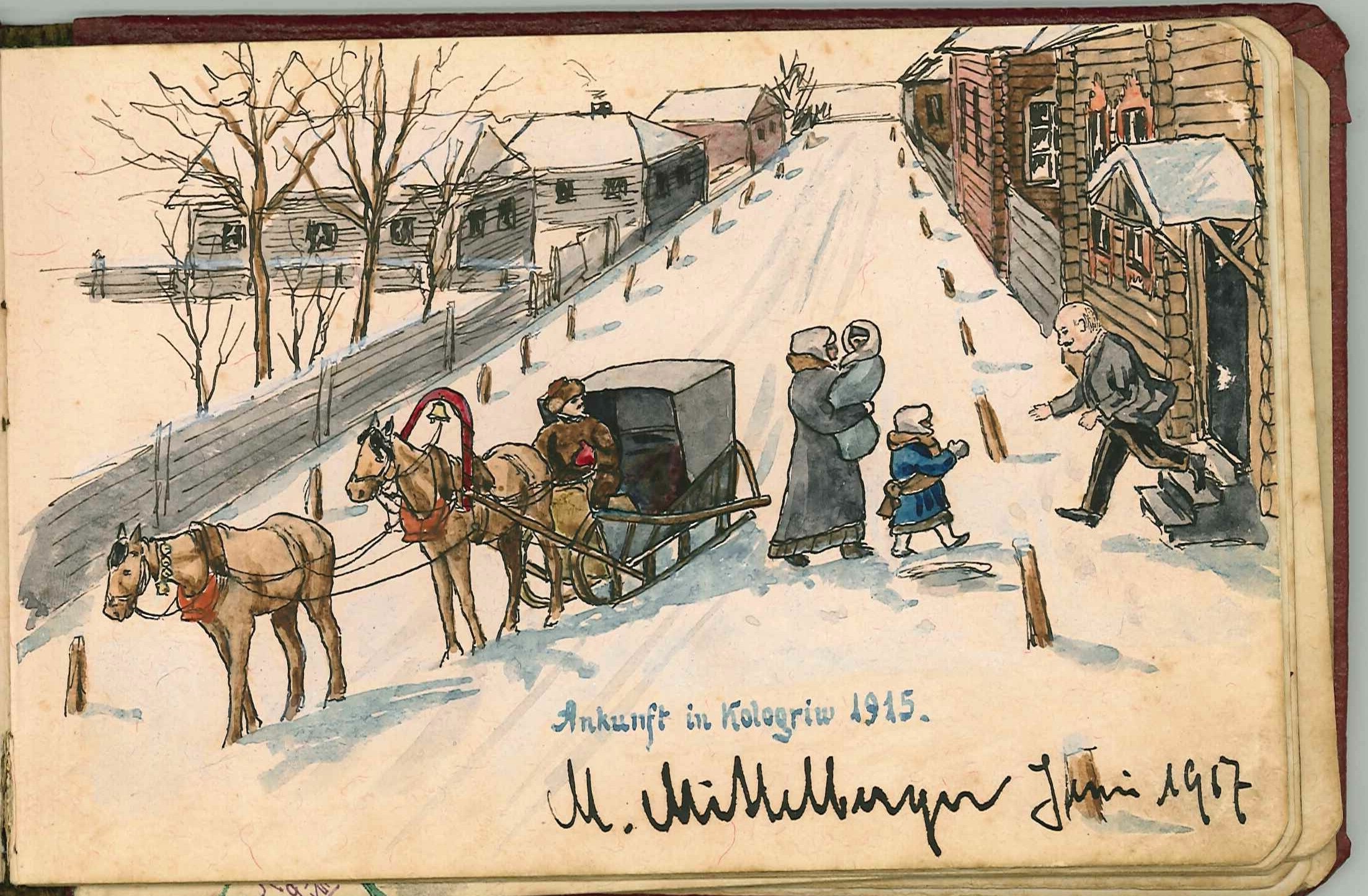

I wrote about something similar in a post a long time ago when I found my grandmother’s old autograph book, remarking:

The autograph book demonstrates a lovely collection of shared sentiments, but at the same time, this generation is collaborating in newly found ways to create.

The tools are always secondary to what is being created. Angela says:

“Our first task is to connect writers to themselves, their needs, their vision for the difference they will make, and their ideas. Who do they want to move with their writing? What is the best way to accomplish this? What’s possible, given the range and access of tools that are available today?” (my emphasis)

Trying out blogging as a platform with year 9 students has shifted something seminal to successful and convincing writing. I was nodding when I read Angela’s words:

“My work involves helping writers develop and share their own. What they are writing has to matter to them. It also has to matter to someone else. Otherwise, they will not persevere as writers. It’s as simple as that. School teachers can force kids to write by threatening them with failing grades. Fortunately, we don’t have that awful luxury at Studio, and I’m grateful for this. It keeps us honest. It keeps our writing real. It helps us persevere.”

In her excellent article Remaining seated: lessons learned by writing Judith M. Jester advises teachers to write if they’re teaching writing.

“As a teacher of writing, I consider writing to

be one of the most important things I can do for

my kids. I need to put myself in their place on a

continual basis so that I more fully understand

what I am asking them to do. How can I know

what difficulties they face if I don’t face them, too?

How will I know what strategies to suggest if I

have not tried them first? How will I know the

joy they experience when they are genuinely

pleased with a draft if I have not felt the same joy?”

It’s a shame that teachers are so busy teaching, assessing and writing reports that they don’t have time to do what they teach. Judith is passionate about the teacher modelling writing:

“What they fail to understand is that they will produce better writers if they pick up a pen for something more than evaluation. If they do, they will learn far more about teaching writing than any instructor’s manual can ever tell them.”

I’m not sure that teachers have much of an opportunity to do much more than keep up with teaching their classes, correcting work and writing reports. The expectation of schools, of a curriculum which drives teachers and students towards the final assessments in senior years so that students enter tertiary institutions of their choice – does this allow much room for senior school teachers to choose between what they want to do and what they must do?

The article gives food for thought. Judith writes about the power of process, the power of feedback, the power of audience, the power of modeling, the power of thinking. Definitely worth reading and thinking about.

Wouldn’t it be nice if teachers’ lives were balanced to allow time for themselves – to think, to try things out, to model what they teach, to alleviate the relentless pressure and give them some space just to be. Teachers should be nurtured as learners too, not just have their last juices squeezed out of them.

Image found here.