It's difficult to process the fallout for students and teachers after two disrupted years of school during Covid19 "iso", and for me it's because there's been no "party" in between. I feel like we've slid in, hopeful but cautious, heads down and no time to stop and reflect. Along the way, random conversations raising concerns about students' lack of motivation or surprisingly low levels of literacy have ended in uncertainty: have they always been this way or is it Covid?

Professional conversations at school continue to focus on rubrics and measurable data, and time is not set aside for a collective reflection and the sharing of what teachers are seeing and how they're dealing with it. But, more importantly, students are being taught the way they always have been, so they scramble and so do we, and that's the way the system works in schools.

Something a colleague and I talk about quite a bit since we both teach VCE English Language (I teach Units 1-2 and she teaches 1-4) is how much - or even how much more - scaffolding our students require when writing essays based on a question, a range of stimuli and wide reading. I say "scaffolding" but it always makes me wince a little. There's something cold and restrictive about the word, something dry and limiting. Still, as much as we both assumed our year 11 students would know how to unpack an essay question and respond to stimuli, we were prepared for their essays to have room for improvement - just not as much room.

And the same for rubrics. Yes, we strive to differentiate, yes we provide feedback (which our students don't read?) but my rubrics, at least, fall short. In the end I feel my rubrics are missing at least half the picture. I've been marking essays and making a checklist of what's missing from the rubrics - too many to fit, although they could be an accompanying checklist. Next term I plan on spending a fair bit of time on essay writing, starting by getting my students to read through their exam essays and tick off what they've done or not done in the checklist. My students are noticeably passive, waiting for me to tell them how to do things; they need to be an active part of the learning process.

These things worry me: Will a student who starts with a significant disadvantage in terms of writing, and who sees low average ratings in the rubric realise that his rate of improvement has been amazing? I can tell him in my feedback, but his focus will be on his rubric rating, that's for sure. And his report will focus on his percentage. Even a 10 in his capabilities for "progress" will not tell him how impressed I am by his effort to take on board my feedback and move forward in leaps and bounds. The rubric still rates him at the lower middle point of the scale, with many of his classmates way ahead of him. Where is the capability for "rising above debilitating lack of motivation" or "getting something submitted even though you're feeling depressed"? These are the human aspects of the feedback students deserve.

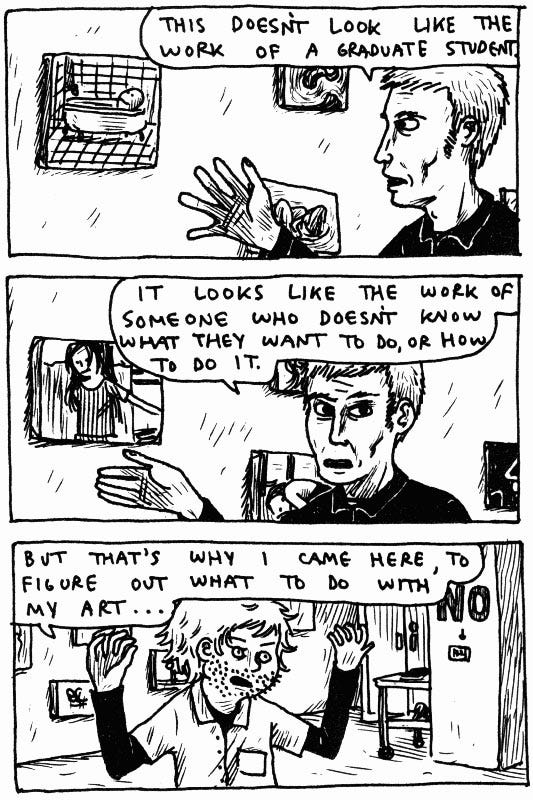

It's not easy to teach writing. At some point in the learning process I provide some model essays from past students. That's not enough in itself although I've fallen for the assumption that it might be. Some students are not capable of picking out from a high quality example what actually makes the writing noteworthy. Should I be doing that for them?

Here are some of the dot points I created for my students as a checklist after reading their English Language essays:

Have you used words precisely?

Have you used the best word for the context?

Have you used colloquial or informal language in the essay?

Have you used words that sound impressive but perhaps you don’t actually know what they mean or how they’re used?

Have you checked your grammar, eg subject/verb agreement or consistency of tense?

Have you used relevant metalanguage when the opportunity arises?

Have you checked for repetition of words, phrases or sentences?

Is your sentence confusing? Is the point of your paragraph clear or confusing?

Does your paragraph include too much/too little (information and examples)?

Flow – can you join shorter sentences and ideas with each other using connectives (and, however, although, therefore)? Or are you making a shopping list?

Are you making too many general statements rather than providing examples and context to support your general statements?

Have you used the best examples?

Have you missed important examples?

Have you forgotten you are focusing on language? Are you going on a rant about issues that do not focus on language or the essay question?

Are you using general, sloppy phrases and sentences instead of making sure you say what you mean in a precise way?

Have you articulated your ideas clearly and then unpacked them comprehensively or is it just an introductory thought that goes nowhere?

Have you used stimulus material to spark ideas or have you just quoted or included stimulus material as your main paragraph content?

Have you paraphrased quotations in stimulus material rather than using the quotation?

Conclusion: Are you using the same words/sentences as previously stated or have you integrated your summary analysis of ideas presented?

Have you included ideas you’ve developed as a result of wide reading or just described what the stimulus material says?

Have you come to your own conclusions or just rehashed what I told you in class? Have you thought/read widely?

I'm torn. I'm aware that teachers need to balance the amount of assistance they provide to students with a certain amount of room for them to work through things on their own so that they learn from that process, otherwise they are so used to us feeding them what they need that they are under the impression that learning is consumption of skills on a platter, whereby they learn things they are given by rote and follow a formula to the end result. Even if that were the case, how engaged would they be? And without engagement they won't have a source to draw from - a source of interest and self-confidence, a thirst to understand and learn more. Isn't that the point of teaching and learning, that balance? What do you think?