My story

The teacher-librarian role is elastic

What I love the most about the teacher-librarian role is its elasticity; it can assume so many different shapes and play out in a variety of stories. In many cases teacher-librarians have come from classroom teaching and therefore bring their expertise and experience, as well as their passion for their methods. My teaching methods were English and LOTE (German and French) and this is what I taught before completing the Master of Education (Teacher Librarianship), however I also have a passion for the Arts, and love supporting and collaborating with teachers in the Arts faculty.

New year, new challenges

Every year I challenge myself to a new project, aiming to forge new relationships with students and teachers while trying out something innovative – sometimes without knowing precisely what until it happens. When collaborating with teachers, I aim to integrate this collaboration over a longer period of time – at least a term, a year if possible. This gives me the opportunity to get to know the students and teacher, and experience their learning/teaching styles firsthand.

This year I approached an art teacher I’d worked with a couple of years ago, with an idea I had been contemplating for some time. Previous experiences in the art classroom had me thinking about two things:

- How can we solve students’ blocks to creativity, and simultaneously broaden their exposure to a variety of art works and styles?

- How can we improve their critical literacies when discussing or writing about art?

The first point stems from my ongoing role in supporting art teachers and students by creating online resources (libguides);and the second point relates to a recent realisation that, if I’m supporting critical literacies, typically by working with English teachers, then why shouldn’t I do the same with those same literacies in art?

Using Medium as a blogging platform

https://medium.com/art-viewpoints

The teacher decided we would work with her year 10 Drawing and Painting class. I suggested to the art teacher that we use Medium as a blogging platform for our purposes. These were my reasons:

- The blog would be the space where we posted all our content and instructions;

- Student blogs would be easily accessible in the followers list;

- Students would be able to read each other’s posts, and respond to them (in the form of ‘clapping’ or comments), resulting in the development of a reading/writing community;

- Images, videos and other media – particularly important in art teaching – could be easily embedded in the posts;

- Our blog and students’ blogs would be situated within a global writing/blogging community, instead of existing in isolation. The Medium homepage (https://medium.com/) is cleverly designed to entice the reader into further reading, based on reading history, as well as your network (as you follow people), and according to your self-appointed areas of interest. In this way students have agency over their feed, in the same way as they feel a sense of ownership while designing their blog.

From archive to targeted post

The Medium blogging platform enabled me to feature online resources I have been creating for years in our libguides. This is exciting because it solves the issue of how to make archived online resources relevant and pertinent to students and teachers. So, for example, when the teacher requested resources about an artist or drawing techniques, I was able to pull these out of the libguides, and the blog post was all we needed for the lesson, easily mirrored on the large screen so students could follow the lesson, or set as homework prior to the lesson in the style of the ‘flipped classroom’.

Medium allows the creation of tabs at the top of each page, and I realised, while thinking about blog design, that I could create tabs for ‘drawing techniques’, ‘artists’, ‘artworks’, ‘critiques’ and ‘teacher posts’ and tag posts accordingly. The blog becomes an interactive resource, providing students with a wealth of resources they can easily navigate .

The blog allows for quick and easy ‘just in time’ posting, so that my role in resourcing becomes ‘live’ when things come up during the lesson and I’m able to create a post on the spot.

A real readership

When students post their writing in response to assigned tasks, they have a real audience, and this is very different to writing for their teacher. They usually feel more motivated to write, to edit their work before it gets published, and because we instruct them to read each others’ posts, they learn from each other. Students are also familiar with the ‘clapping’ (liking) and commenting options which are ubiquitous on all social media sites, and they enjoy being connected to the class, motivated also by the possibility of attracting a readership outside the school. Of course, it’s my job to monitor the appropriateness of all interactions.

Digital literacies

In the first lesson, I spoke to students about the implications of being published externally. The acceptable behaviour policies are permanently in the blog’s archive for students to revisit, or to use as gentle reminders. I also posted ‘How to comment on someone’s writing in an online environment’.

Commenting is actually harder than it first seems. Writing a ‘comment’ following another student’s post is much more than the monosyllabic or gif-laden comments on social media; it involves an understanding and evaluation of the post, and an articulate, constructive observation or even extension of the original ideas. These are additional literacies which, if not taught explicitly, or practised, will not be developed.

Critical literacies in art

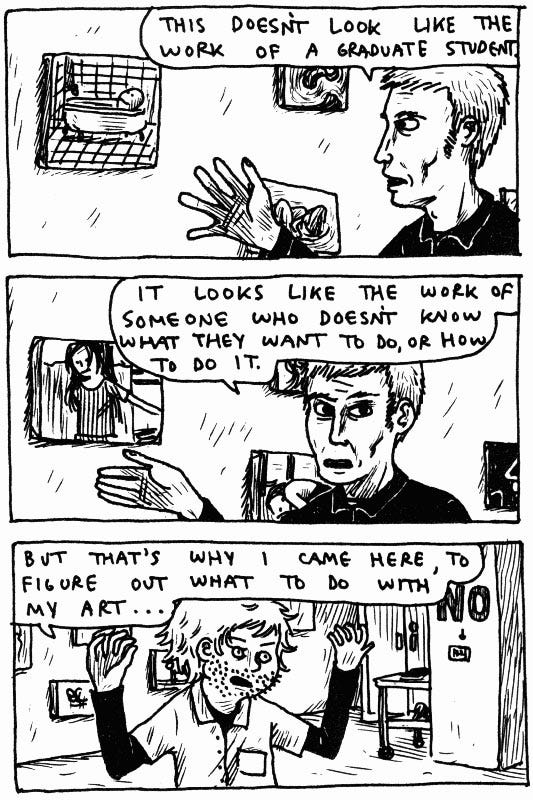

We sometimes forget that critical literacies have been taught explicitly in art even before they gained prominence in our students’ skills set. In art, these critical skills develop as students learn to see, then unpack, discuss, and finally, write about an art work. Blogs lend themselves to short ‘lessons’ on what this might look like. For example, I posted: ‘How to critique someone else’s art work’ which begins with a light-hearted cartoon, and then shows a video created by ‘The Art Assignment: PBS digital studios’. There is so much relevant media freely available online on this topic, and it’s the teacher-librarian’s role to sift through and carefully curate the best resources for the class, as well as for the teacher. On the same topic, I also posted: ‘Ways of seeing and writing about art’, in which I included a video from Smart History, as well as one entitled: ‘How to understand a Picasso’. This kind of resourcing is time-consuming; teachers always appreciate teacher-librarians’ help in this area.

Progress so far

Despite being in its early stages, our digital resource is growing in leaps and bounds. I appreciate being informed by the teacher’s and students’ needs which arise during class time, so that the blog evolves organically and often at point of need. I find this works so much more effectively compared to my earlier experiences of emailing the teacher to ask how I might support her. My participation in classes has resulted in so many more ideas, and our collaborative teaching and conversations during class inform my work. As we play off each other during the lesson, ideas are generated in the most productive and creative way.

What is it about the blog…?

Since working with blogs in classes from 2008, I’ve had a chance to reflect on what works well and how to innovate for even better results. I think that the separation into posts of what might become too dense and difficult for students to take in, is one of the advantages of teaching and learning this way. Tags, categories (tabs), hyperlinks – help students take in digestible amounts, and enable them to follow hyperlinks to further reading if they wish, or navigate the site to find what they need to revise content. These are the digital literacies teacher-librarians will often teach, and in this way we are not teaching them in isolation, but in context.

Differentiation

When providing extension material for students, the blogging platform allows teacher-librarians to provide differentiation by posting content for depth and breadth, and tag posts accordingly. In art, there are always more examples and opportunities to expand students’ horizons with more artists, more techniques, art history, local exhibitions, art from featured museums and galleries, and articles or videos/podcasts about art issues. I’ve shared a range of broad and issues-based posts, eg. ‘Who decides what art means’; ‘Women artists and their struggle’; ‘It seems art can help you if you’re studying to become a doctor. Does that surprise you?’

Projects such as this one have me thinking about the tragedy of staffing in some school libraries. Even with well staffed libraries, teacher librarians might not have the opportunity to explore and experiment. Some of my most valuable experiences have developed from a mere hunch that something worthwhile might eventuate. Frankly, there is always a positive outcome when you experiment with the stretchiness of your role, even if it’s not what you expected. As I said earlier, the teacher-librarian role can play out in a variety of stories, all as diverse as we are. Let’s hope that we hold our ground in schools so that we can prove our value.

This article has been published in the SCIS ‘Connections’ magazine.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=dd9ba1b7-c973-4b7b-bbbc-db661c7dfac4)