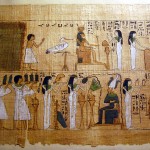

The Independent featured an article with this poignant question – can intelligent literature survive in the digital age? As the article says, ‘Is the paper-and-ink book heading the way of the papyrus scroll?’ This is indeed a question worth devoting more than a couple of minutes to.

The crucial question is – whether all our online reading – the fragmented, stylistically-challenged emails and microblogging – has taken its toll on our attention span? Nicholas Carr of ‘Is Google making us stupid?’ fame has added to the debate by claiming that the internet is responsible for his downward spiral in longterm concentration: ‘Once I was a scuba diver in the sea of words. Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski.’

Scott Karp, who writes a blog about online media, claims he used to be a voracious reader, but has now stopped reading books altogether. Is the internet to blame? Other people quoted in this article admit that they are now unable to concentrate on more than a couple of paragraphs at a time, and that they skim read, rather than read and think deeply.

A recently published study of online research habits , conducted by scholars from University College London’ claims the following:

‘It is clear that users are not reading online in the traditional sense; indeed there are signs that new forms of “reading” are emerging as users “power browse” horizontally through titles, contents pages and abstracts going for quick wins. It almost seems that they go online to avoid reading in the traditional sense.’ Still, the article does maintain that we are reading more now than when television was the preferred (only?) medium. Personally, I find it difficult not to skip around when links abound and I’m torn between too many tantalising directions.

Carr supports this behaviour with the following observation:

‘When the Net absorbs a medium, that medium is re-created in the Net’s image. It injects the medium’s content with hyperlinks, blinking ads, and other digital gewgaws, and it surrounds the content with the content of all the other media it has absorbed. A new e-mail message, for instance, may announce its arrival as we’re glancing over the latest headlines at a newspaper’s site. The result is to scatter our attention and diffuse our concentration.’

But is this fear of change typical of the fear each generation experiences?

‘In Plato’s Phaedrus, Socrates bemoaned the development of writing. He feared that, as people came to rely on the written word as a substitute for the knowledge they used to carry inside their heads, they would, in the words of one of the dialogue’s characters, “cease to exercise their memory and become forgetful.’ That may be so, but in today’s ‘information age’, it would be foolish to try to carry all the knowledge we read inside our heads, especially when access is so easy.

If the internet and Google are wired for quick knowledge-access, then surely, we realise that we don’t just read for knowledge. We read fiction, for example, as we regard art, to enter into a transformed, deeper(?) reality; to savour language and perceptions; to gain insight into the human condition; to gain moral, social and philosophical truths; to experience many things besides.

Are we losing/have we lost something in our move to 21st century literacies? Is it a matter of a lost language or genetic traces that will never be repaired? Even avid readers will necessarily read less traditional, hard-copy literature, if only because they are also keeping up with blogs, wikis and RSS feeds? Are we becoming ‘pancake people’, as the playwright, Richard Foreman, suggests?

Now, according to The Independent, many serious writers complain that challenging fiction doesn’t appeal – “difficult” novels don’t sell. To sell now, ‘books evidently need to be big on plot and incident, short on interior monologue.’ What are the consequences for teachers and librarians, trying to encourage young people to read? Are we trying to keep grandma alive? And besides, if we admit it, our own reading patterns are changing to some extent. And yet, websites that give exposure to books can only increase readership. Just think about all the literature you might be tempted to read after reading somebody’s passionate review or after searching Google Book Search.

If only you had the time or could get off the internet!