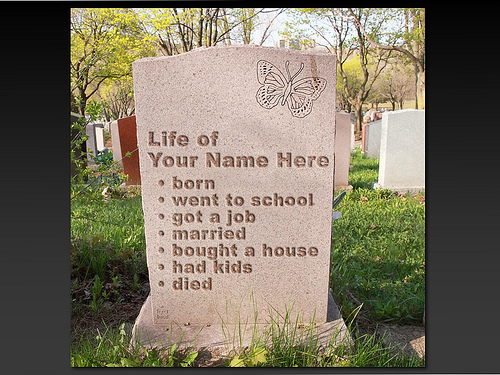

I firmly believe that we should educate students for their world.

There’s no doubt that they will function in an online and networked world, even more than they are doing now.

Yesterday our staff listened to Susan McLean’s talk about the dangers of the cyberworld. I became increasingly uncomfortable as the horror stories unfolded at the expense of a more balanced view, or even in terms of focusing on how we could manage cybersafety education.

I want to share my letter to the principal in the hope of opening up a conversation which will fill in the gaps to create a balanced picture of what we should be doing to educate our students as citizens of their future world.

To balance out last night’s presentation on cyberbullying, I would like to suggest that you look at ACMA which provides excellent links to resources and free PD.

For example, here is the page for teens with practical help

You can browse the site – it is set out clearly, and very helpful.

I hope that our staff have been discerning in understanding that Susan McLean has presented a very extreme picture, describing the worst case scenarios (many of them), which should be acknowledged for what they are – worst case scenarios. It was difficult not to be affected by her stories; I know I was starting to panic and my instinct to run and save myself kicked in.

What was unmistakable – Susan only mentioned that online involvement could be positive at the beginning and end of the presentation – she didn’t give examples. Her language was emotionally charged, and her numerous horror stories were dramatic.

It would be a shame if staff who were already resistant to technology and strangers to online possibilities in education, were to run even further away from technology – especially as we are a laptop school. We have to remember that we are educating students for their technology-rich world, not our world or the world of our own schooling.

Just yesterday I was moderating comments in my fiction blog – no comments will be published until I approve them. I’m encouraging comments to inspire discussion around books and reading, and I noticed a student had commented on a student review of the new Harry Potter movie. The comment was fine, but the last sentence inappropriately put down a boy who had received a scholarship. I found the boy, had a little chat with him about what was inappropriate in the comment (he understood), and asked him to resubmit the comment without the negative part. This is part of students’ ongoing education – who else will teach them how to behave online if we don’t?

We need, more than ever, to understand the power of these technologies, and educate our students to use them responsibly. The only way we will understand these from the inside is if we play with them ourselves. I would be more than happy to show you my Facebook and Twitter involvement – they are an important part of my professional development and educational support.

What is also imperative, is that we don’t mix up the problematic online activities of our students in their leisure time with the technology that can be used to support teaching and learning, eg. Blogs, nings, etc.

When you have time, please have a look at the 7M ning – we are thrilled to have Allan Baillie, author of our literature study, ‘Little Brother’, as part of our ning, ready to join the students in discussion. What better way to learn about the book than have the author answer questions – this is authentic learning. The boys and Maria and I are excited that Allan has agreed to join us, and we spent yesterday’s lesson reading his life story on his website in preparation for our interaction with him.

I hope you accept my email in the spirit it has been written. I believe that we need to educate our students for their world. We should not bury our heads in the sand, but accept the challenge, moving past our own discomfort with technology, and taking up our responsibility to educate responsible citizens.

Thanks to Lisa Dumicich for the link to ACMA on Twitter.

I would be extremely interested in hearing what you think about this issue of cybersafety and the use of Web 2.0 technologies in education. Please enter into the conversation.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=23dc1b8a-d323-4ca3-9174-1a7851a0330d)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=dd9ba1b7-c973-4b7b-bbbc-db661c7dfac4)