Yesterday I unexpectedly leaped into a heated argument with a very close friend who had come to visit from interstate. It was one of those fires that flare up suddenly from a small spark, blazing fiercely long enough for onlookers to look alarmed and consider calling for help, and then burn down gradually, leaving those involved in a slightly shaky state, surveying the damage.

The offending spark was a question about why my friend’s daughter didn’t have Facebook, and if she did I’d be able to view her photos from the Ball she was attending that night. Remember, these friends live interstate.

Now, you can imagine, with a blazing argument, most of what goes on is reactive, and each person becomes locked in to a mainly defensive position, taking each comment personally and wanting to come back strongly enough to defend their position. There isn’t any room for thought or even fair appraisal of what the opponent has said. Luckily, the latter occurred as the fire burned down; concession and reconciliation was possible in the smouldering stage.

I can only speak for myself in this argument, and I will.

I reacted to my friend’s initial painting of Facebook and MySpace as bad places (which, I think, he must have said unconsciously, because he later denied it), places where, at best, young people wasted their time with inane conversations, and, at worst, young people exposed themselves graphically involved in the worst behaviour.

If I hadn’t been so defensive, I would have said that I’d been there not so long ago. I was initially against my older son interacting online, either msn or Facebook/MySpace. I gave many reasons, but one I pushed the strongest was that online interaction was not real, it was virtual. It was unnatural, it took away from the time spent with people face to face, it was potentially dangerous because it increased solitary time with virtual friends, etc. Why didn’t he use the phone if he wanted to talk to someone? How could he be ‘friends’ with all those people? That wasn’t friendship.

Funnily enough, these were some of the points my friend expressed, in between dodging my line of fire. I wonder (always wonder) when I’ll learn that the conversation ends when the other person feels attacked.

What has happened from the time I held my friend’s convictions and now? Several things. Instead of making conclusions about social networking and online environments from the outside, based on what I’d read, on media reports (which are mainly negative and engender fear in parents and teachers), I decided to play around with these things myself. What happened? I connected with people I hadn’t talked to for years (even decades), I saw photos of where they lived, saw status updates of what they were up to – no, not just what they had for breakfast – they were about to become parents, or they were travelling overseas, etc. No, I didn’t have deep relationships with all of these people, but I did appreciate suddenly having a general view of what my ‘friends’ were up to, and many of these are scattered all around the world.

I also saw a different side to young people, definitely different to the picture that is often painted in the media, or even in conversations held by people who have little to do with adolescents or university-age students. I saw these people supporting each other with positive comments, engaging in humorous and often witty dialogue, planning events and meetings, putting out interesting links to things they had read or music they listened to, venturing to express opinions they might not in real life.

One of my main points in the aftermath of the argument was that social networking supports real-life interaction. The young people I observe are less isolated than I used to be at their age, not only because they can chat to a group of friends at home in between homework, but because they use these connections to meet up and do something together. They inititate interest groups, they gather friends for events, they learn to function as social beings – important skills for life and work. They do this because these spaces belong to them. They’re not forced to create a group and contribute to discussion; they choose to because of personal interest.

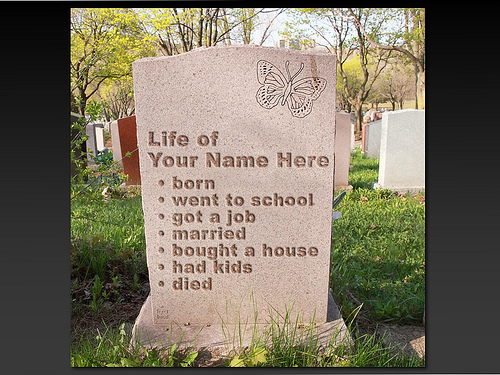

Which brings me to my next point. How much of this initiative and cooperation do we see in schools, in the classroom? Do we see discussion, do we see young people sharing their interests and passions? Or do we see disengagement, boredom, solitary struggle in place of collaborative effort? Is there room for students to take initiative, pursue interests, work together to solve problems, get involved in real-world research and enquiry.

Are we getting the best out of our young people at school?

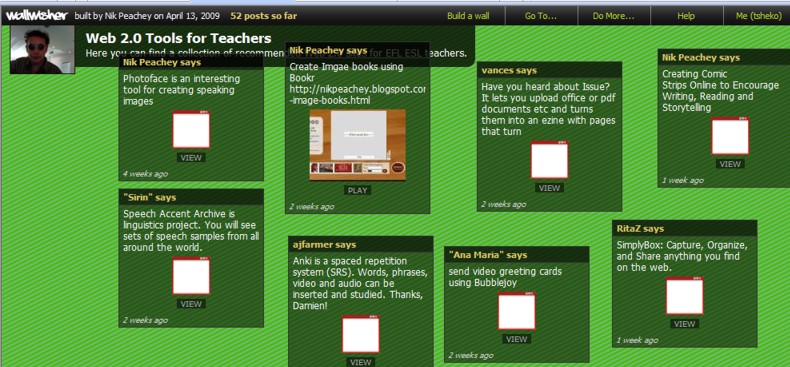

To finish my rave, yes! I agree with my friend that there is potential danger in online involvement. And I believe we should discuss these dangers. We should take every opportunity to educate our young people about the irreversible nature of what they put out the web. But we could also create a safe, online environment for them to use at home when they need help with homework, or when they want to share ideas for a project. A place they could become teachers as well as learners. An exciting place where they are enriched by the diverse contribution of others. Where they learn to respect each other. Where they are not afraid to ask questions.

As an educator, I’ve been pushing my boundaries, often painfully, against what I felt comfortable with. But I want to keep my eyes open, and I’m trying to re-evaluate constantly, and I know that I must do that if I’m to have any part in educating young people for their future. No, not going with all the latest fads, not embracing new things without thought, but thinking deeply, and listening to the dialogue in my own online network, asking the deep questions….

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=23dc1b8a-d323-4ca3-9174-1a7851a0330d)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=dd9ba1b7-c973-4b7b-bbbc-db661c7dfac4)