Art21 blog has given me an interesting idea in their latest post:

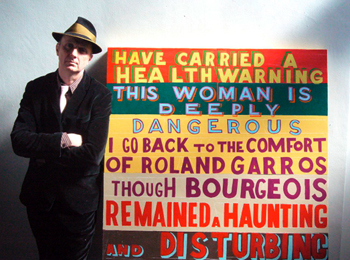

Last year the Guardian asked its sports and art writers to swap pieces for a day. Tennis correspondent Steve Bierley reviewed a Louise Bourgeois (Season 1) exhibition, which Bob and Roberta Smith fell in love with and subsequently made into a text-based painting.

Hmmm…

But how can we translate that into the school environment? I mean, the idea is something I’ve been playing with for a while – wouldn’t it be good if school didn’t separate learning into subjects?

Life isn’t like that, so why….?

In my job as teacher librarian I write a blog to encourage reading – I’ve mentioned it before – well, it’s not only about reading but all that goes with it. Thinking, discussing, idea-broadening, understanding – you know what I mean. Ideally, I’d love for the blog to create a reading (thinking, etc.) community, one that links people within the school through interests and discussion, but also links the school community with the wider community. I’ve also spoken about this before. Yes, I have so far included a couple of book recommendations/reviews by teachers who aren’t librarians. This is good, this gives the students the idea that people outside of the library read and enjoy reading. But …. they’re English teachers.

What I would really love is if sports teachers wrote about their reading. Yes, sports teachers. Maths teachers. Legal studies teachers.

So what kind of swap could I do? Do you think it would be easier for the maths/science teachers to talk books than the other way around? At first I thought yes. What’s left of my own maths/science knowledge, the little I gained in secondary school? I wouldn’t really like to go there. But then I remembered Sean Nash. He blends Science with the Arts. I was overwhelmed by his approach when I first discovered Sean’s blog, and I continue to be overwhelmed because it’s so inspiring, and I don’t see many educators do it.

Sean’s wife, Erin, shares his way of looking at a blended curriculum. Have a read of Erin’s profile on Sean’s biology ning where she says:

- The best thing about the study of biology is:

- The opportunity it provides for invoking curiosity and questioning in students and instructors alike. There are so many interesting topics in Biology that, ultimately, bring about questions that just aren’t currently answerable, and this provides so many awesome possibilities for critical thought and analysis. I could have taught English or Biology, and I was drawn to science because of that one big question, “WHY?”

Isn’t this also the point of literature? The WHY and WHAT IF? What if a character lived in a particular time/situation? How would that character live out his/her life? And WHAT IF this complication arose? WHY would he/she act in that way/make those choices? Personal choices, ethical choices, any choices.

I frequently reflect on what I’m trying to achieve in writing the fiction blog. Why is it important to stretch students’ – and for that matter, teachers’ – concept of what a reader is like, why we read, why books grab our attention, how books and films get our reactions and lead us into discussion or debate. It’s not a library thing, it’s not an English thing – and yet, it is literacy. The kind of literacy that is important for all of us across disciplines and beyond school. Sean Nash sums it up excellently when he talks about the connection between science and literacy in his comment to my post:

Science and literacy had certainly better go together. We are in a heap of trouble as a species as it is. We can’t afford to continue to create a scientifically-illiterate populace. Where science and literacy are separate, science is but mystery and mythology to even our brightest.