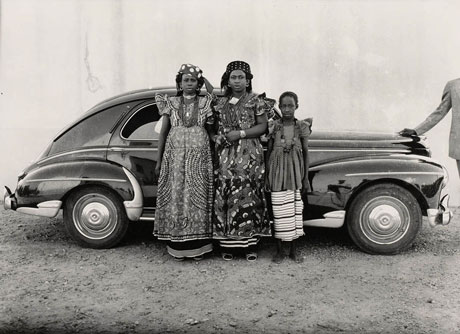

Photo by Alexander Sheko

This blog post led me to a New York Times article (13 Sept. 2014) by Stephanie Rosenbloom : The art of slowing down in a museum.

There is something in this message that speaks to me about Connected Courses. Many of us have already remarked that the course is bursting and exploding with the wonderful shared information and ideas. Mia Zamora even made sure, at the start of the course, that we acknowledged it was a guilt free zone. We were encouraged to dip in and out of things that spoke to us rather than tick off a (massive) list in a course which isn’t actually linear.

For me Connected Courses have been the most valuable and inspiring form of professional development – maybe ever. I even wished I didn’t have to sleep so I could keep learning and stay in the conversations that were mainly happening in different timezones to mine. But at the same time I feel like a child who is overwhelmed by too much choice, and currently I’m aware that I’m running from this to that, not staying too long in case I miss out on something.

At times I feel like I’m skimming the surface; I would also like to go deeper. After all, there should be more times when I stop feverishly multi-saving to Diigo/Pinterest/Feedly and sit down to digest some things at a reflective pace.

The art of slowing down in a museum really resonated with me, and I started drawing parallels between looking at art works and reading and watching what the Connected Courses community shares.

If the average visitor spends 15 to 30 seconds in front of a work of art, according to museum researchers (as stated in the article), how does this compare with the amount of time we spend reading (and thinking about) shared blog posts or articles? If we tweet out an article or post so quickly that it becomes obvious we couldn’t possibly have read it properly, or at least read it deeply – and I’ve done that many times (even halfway through reading) charged by a passionate response and the desire to share – then are we being too superficial, and should we just take the time to read one thing more deeply?

Does ‘the breathless life of the Internet age conspire to make that feel normal?’ There is no doubt that our behaviour on social media is fast paced. ‘But (as stated in the article) what’s a traveler with a long bucket list to do? Blow off the Venus de Milo to linger over a less popular lady like Diana of Versailles?’ How much breadth do we sacrifice for depth?

Professor Pawelski, who studies connections between positive psychology and the humanities, states that people who visit an art museum quickly and look at art in the same way as they might tick off a large reading list of books, see as much of art as you would if you read books by looking at their spines. He says that ‘ if you do choose to slow down — to find a piece of art that speaks to you and observe it for minutes rather than seconds — you are more likely to connect with the art, the person with whom you’re touring the galleries, maybe even yourself’.

So I’m thinking about my own behaviour in Connected Courses, and reflecting on how much I slow down for, and how deeply I’m engaging with thematic offerings. Of course, we don’t always have the luxury of unlimited time when we’re all juggling #ccourses with work and life, but it’s good to stop and reflect.

As a teacher librarian I’m like a squirrel gathering the goodies and adding to the stockpile so that I can curate best quality resources across the curriculum, or provide teachers with exactly what they want at point of need. But finding resources is only one part of my job, and I’m convinced that ‘connecting with the art’ in a way that enables me to connect with myself – metaphorically speaking – will benefit the teachers and students whose learning and teaching I support.

When Professor Pawelski asks his students to spend 20 minutes in front of a single painting, he is confident that they will actually begin to be able to see what they’re looking at. The article also includes an interesting anecdote about Dr Julie Haizlip, a scientist and self-described left-brain thinker, who was a little skeptical about this exercise, and who confessed that she ‘had never spent 20 minutes looking at a work of art and prefers Keith Haring, Andy Warhol and Jackson Pollock to Matisse, Rousseau and Picasso’. ‘Rather than check master works off a list as if on a scavenger hunt’, the exercise aimed at finding an art work that resonated with her on a personal level.

At first nothing grabbed her attention but eventually ‘she spotted a beautiful, melancholy woman with red hair like her own. It was Toulouse-Lautrec’s painting of a prostitute, “A-Montrouge” — Rosa La Rouge.’

Source: Wikimedia

“I was trying to figure out why she had such a severe look on her face,” said Dr. Haizlip. As the minutes passed, Dr. Haizlip found herself mentally writing the woman’s story, imagining that she felt trapped and unhappy — yet determined. Over her shoulder, Toulouse-Lautrec had painted a window. “There’s an escape,” Dr. Haizlip thought. “You just have to turn around and see it.”

“I was actually projecting a lot of me and what was going on in my life at that moment into that painting,” she continued. “It ended up being a moment of self-discovery.”

Dr. Haizlip had been looking for some kind of change in her professional life but wasn’t sure what. Three months after looking at the painting, she changed her practice, accepting a different position. She said:

“There really was a window behind me that I don’t know I would have seen had I not started looking at things differently.”

We have so many interwoven responses to the weekly themes in Connected Courses – so many wonderful perspectives, and so many engaging conversations, so many ‘aha’ moments. The value of the course is the community: the human interaction. It really isn’t about the content as much as the energy and elucidation which comes from connections within the cohort. It’s messy, and it’s frustrating – because we can’t capture everything or follow something to its neat conclusion – but it’s exhilarating. But if we don’t stay long enough in a post, article or webinar, if we don’t grow the personal connections, we’ll miss the meaning that is ours. Reading other’s reflections is not the same as looking for our own.

And while I secretly want to read everything (and capture it forever in my carefully crafted bookmarks and boards), I know that I need to let go of wanting the whole lot in order to focus more deeply on what speaks to me, and stay for a while, playing with others in that space.

Might you miss some other works by narrowing your focus? Perhaps. But (as Professor Pawelski put it), sometimes you get more for the price of admission by opting to see less.

Vilhelm Hammershøi - interior, young woman seen from behind (1904)

The

The