Well, hello. Haven’t been around the blog lately. Mid-year holidays and taking time out of my head for a change. And, to tell you the truth, I’ve needed the break. No blog ideas put up their hands in their usual impatient manner. Nothing was hammering inside my head, clamouring to come out. No clear thoughts were forming, no ideas were sprouting. For a while there, I thought I’d dried out for good. Until I realised that I was looking back, only I’m not sure if I’m having second thoughts, or if I’m giving things a second look over.

Our PLP presentation is very close now. I can’t deny feeling unprepared. How have we, as a team, moved forward in changing teaching and learning in our school? How far have we come, if at all?

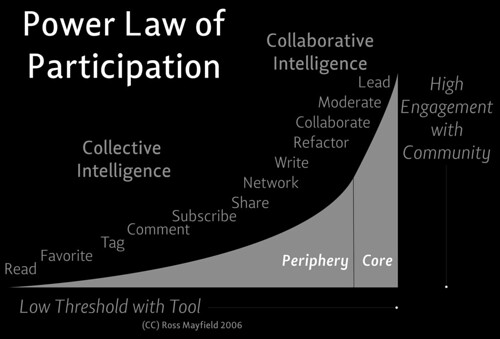

The answer is simultaneously a great deal and hardly at all. Taking part in the PLP ning, connecting to a rich network of educators, great minds, variety of personalities and viewpoints, forming a personal learning network that I don’t feel I could do without – this is a new dimension that has changed my life as a teacher and a learner. The Art and English wikis, the personal and reading blogs, the ning I created to support students and teachers at my school are initial experiments, attempts to engage students in new ways, to share resources, to present different types of media as possibilities for discussion or creativity, to use technology for the purpose of re-envisaging education.

But how far does this go in making any difference to the way teaching and learning occur at my school? How many eductors have seen these things, and if they do, how many are convinced that I’m offering them something valuable, something worth trying out? The answer is – not many.

Dean Shareski’s post has resonated with me today. He describes the architecture of learning as transformative where there’s no going back.

The landscape of learning is changing. Rethinking what control means, understranding the power of sharing and transparency all work to topple many of the foundations our schools are built upon.

His post strikes a chord with me at this stage of my journey:

I know this, you know this but after spending 3 days amongst 18,000 in the educational technology field, I still say very few else know this. I made this observation (jump down to #4) last year at NECC and while the number may have increased slightly, those who really have any sense of the changes that are possilbe and perhaps inevitable in education is strikingly small. Yet sometimes the conversations amongst them would indicate they think everyone understands. A good example took place in the last session I attended on a panel discussion on Web 2.0. The panel was made up of all people that I and many in the audience knew very well either because we’ve spent time with them or know them from varoius online circles. The panel and audience were calling them by their first names and having a good discussion One lady stood up and felt frustrated since she didn’t know these people, these terms and most of the content of the conversation. That wasn’t her fault that’s ours. The assumption amongst folks who live and breath social media is that most teachers know about but they just don’t understand social media. We jump in with disucssion about Web 2.0 when they aren’t ready for that discussion since they have absolutely no prior knowledge. I”m not against having these kinds of discussions but it’s a bit like Christopher Columbus and crew arguing over how they would organize and structure the new world when most of the old world didn’t even know it existed and if they did, had no idea why or how they would get over to see it, let alone settle there. It’s not a totally useless discussion but perspective is important.

This is what I’m finding unsettling at this stage – Dean’s analogy with Columbus. Should I feel unsettled knowing that I’m trying to populate a new world with people who deny its existence? Am I going about this the wrong way? Should I be happy to go slowly with a minority of takers? Am I being naive and unrealistic? Is trying to change teaching and learning in a school insane or egotistical? Am I unrealistically trying to change society itself? Can individuals make this change or is it only possible for politicians?

But then again, I’m pulled back by a comment on Dean’s blog by a teacher who attended NECC:

I paid my own way, as did many of the classroom teachers and a few of the administrators I met, because we are hungry to learn and starving for people who have the knowledge and experience to teach us. Of course, there were sessions and conversations at NECC that were way over my head, but hearing them and trying to understand gives me guideposts and goals for my future development.

If my new, recent direction in learning and teaching came ‘out of the blue’, then why shouldn’t other people make that transition? If a teacher cares about students and thinks about the best ways to inspire students to learn, then who’s to say my little steps, and those steps of my fellow PLP members, or anyone else who is struggling through relevant and engaging teaching and learning – who’s to say these things won’t make a difference?

Should we despair that our efforts are mere drops in the ocean, or should we appreciate our small steps? So many rhetorical questions…

Dean points us to Tom Carroll’s article, If we didn’t have the schools we have today, would we create the schools we have today? written 8 years ago and still very pertinent:

If we continue to prepare teachers as we have always prepared them, we are going to continue to recreate the schools we have always had. We have to start preparing teachers differently. If we are going to continue preparing educators to work as solo, stand-alone teachers in self-contained, isolated classrooms, we are going to perpetuate the schools we have today. If we want schools to be different, we must start today to prepare teachers differently… significantly differently.

Yes, I do feel a few can make a difference, but it’s a slow and laborious process. Why isn’t teacher training aligned with the educational needs of students today? Who should we be influencing in order to revise teacher training, in order to go to the source of the problem?

I might stop before another flood of questions is unleashed. Please come in and help stop the flood.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=3f4f6098-1314-4c49-8be4-0a90409a7b97)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=dd9ba1b7-c973-4b7b-bbbc-db661c7dfac4)